Functional Programming, Abstraction, and Naming Things

Some years ago - never mind how long precisely - having little or no money I

found myself as a teaching assistant for an introductory course in algebra. In

an event that I still recall, the instructor gave a lecture about the

fundamentals definitions of a topic known as group theory. For those that

don't know, a group is an algebraic structure that consists of a set of elements

together with an operation that combines any two elements to produce a third

element; and where the operation satisfies four equational laws. The lecture

was straightforward, but afterwards a student walked up to me and asked me

question:

So what's a group ... actually?

That's easy I thought, I'll use the usual metaphor one uses to describe groups:

modular arithmetic or clock arithmetic. If the hour hand of a clock is at 9 and

4 hours is added to it it loops back around to 1. One can never add time to the

position outside of the 12-hour cycle. The addition of time always proceeds

equally forward if equal intervals are added. If one advances the clock by no

time, it remains at the same position. And regardless of what time you're at

there's always some interval of time you can add to get to any other point in

time.

This is a vague metaphor-heavily description of what a group is. More precisely

it's defined to be a combination of a set $\text{G}$ and an operation $\star$

written as $(\text{G}, \star)$ with four laws:

Law Description

Closure For all $a$, $b$ in $G$, the result of the operation, $a \star b$, is also in $G$.

Associativity For all $a$, $b$ and $c$ in $G$, $(a \star b) \star c = a \star (b \star c)$.

Identity For any element $a$ in $G$ there is an element $e$ where $e \star a = a \star e = a$.

Invertibility For each element $a$ in $G$ there is an element $b$ where $a \star b = b \star a = e$, where $e$ is the identity.

Groups are an extremely important concept that are integral to next generation

of elliptic curve

cryptography that

protect our internet transactions and banking, and on top of that show up

constantly as part of our underlying description of the physical laws of the

universe itself.

After a half hour explanation of clock arithmetic, examples over the integers

and hand waving wildly at blackboard, the student then asked me:

I understand the equations, but what's a group actually?

At this point, I didn't have much else to say. There really is nothing I can

say, other than that a group is the set of equations, I can't point at

something in the classroom and say that this object fully embodies

"groupiness", nor can I pull out a dictionary and find a synonym for group that

would in any way convey the essence of what a group is. Common English simply

lacks a word for "set with operation satisfying closure, associativity, identity

and invertibility".

The concept is not particularly hard in retrospect, and indeed after a bit of

quiet contemplation the topic eventually clicked for the student and she

eventually went on to take other classes in higher mathematics, in particular

Galois

theory

which builds on these foundations. Since then I've left teaching math behind me

and gone on to programming in industry.

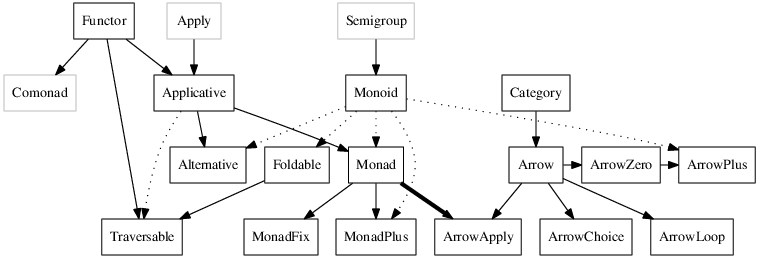

So why do I bring this up? Groups, like many concepts in functional programming,

are often some of the first concepts that we encounter that defy a reduction

down to our everyday experience; and are a constant point of confusion because

of it. Yet, for as long as I've been involved with industrial programmers it has

been a constant point of contention that the names used in describing concepts

like Monad, Functor, and Category are problematic because they don't convey

immediate (partial) understanding by reducing them down to concepts from our

everyday experience. This thinking is not all that dissimilar from the mental

gap that the student studying groups for the first time had to overcome.

I understand the functions and laws, but what's a monad actually?

A monoid (or pick any of your favorite Haskell abstractions) is typically a

small interface defined over a set of types that satisfies certain laws. This

style of designing abstractions is often quite foreign in programming in the

large, and other schools of thought (see Gang of

Four) actively encourage weaving

cryptic metaphors and anthropomorphising code as a means to convey structure.

Law Description

Left Identity mempty <> x = x

Right Identity x <> mempty = x

Associativity (x <> y) <> z = x <> (y <> z)

The argument that Monoid should be called something else (maybe Appendable) is about

as convincing as the proposition that a Group should be Clock. A clock in a

contrived sense can be considered a group and perhaps helps with some initial

intuition, but the term is ultimately misleading. Similarly, if one expects that

all constructs in programming be modeled on everyday concepts one will

eventually hit up against the limitations of everyday experience to model higher

abstractions. We would never arrive at complex numbers by counting scratches on

a clay tablet, nor will would come up with Galois theory or elliptic curve

cryptography by considering groups purely in terms of clocks.

The algebraic terminology was invented often hundred of years ago and is

effectively arbitrary. Therein lies the strength though, it's intentionally

precise because it doesn't come muddled in the baggage of everyday experience,

which can confuse and mislead (i.e only special monoids have an append-like

operation in their definition). Using the terminology of mathematics opens up

hundreds of years of progress done by thousands of people discovering results we

would never think of on our own. And on a larger scale often opens up

surprising

results

mapping between different disciplines and computer science.

Dijkstra's quote is quite apt: "The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague,

but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise."

Programming with precise algebraic names and equational reasoning is here to

stay, and the edifice of abstraction is only going to grow as programming

becomes more precise and refined.